008 | The Demon of Disease

008 | The Yaksha Maha Kola Sanni | Illness, myths, and the Spirit World

This episode explores one of the most complex and misunderstood figures in Sri Lankan folklore: Maha Kola Sanni Yaksha. Drawing from an 1866 journal entry published by the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, we trace the origins, transformation, and interpretations of this spirit across time.

How did a child born from injustice become the ruler of 18 yaksha associated with disease and madness? What do these stories say about the way illness, mythology, and the supernatural were understood in ancient Lanka—and what still lingers today?

We also highlight the Sanni Yakuma ritual—not just as a performance or a healing ritual, but as a cultural response to suffering that draws on humour and community to manifest beliefs.

Listen to the Myths & Samsara podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, and Pandora.

Below is the transcript organized as an essay with references at the bottom of the page.

Introduction

Today’s story comes from an Excerpt from the Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 4, Colombo Apothecaries Company, published in 1866.

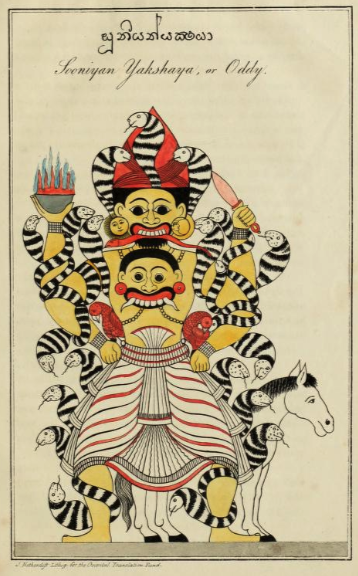

Maha Cola Sanni Yakseya, or the Great Yaksha of the fatal diseases, according to one account, sprang into existence from the ashes of the funeral pile of Asoopala Cumari, a princess of the city of Wisala Maha Nuwera. Wisala Maha Nuwara is translated as the ‘great extensive city’ and is referred to in many folkloric stories. However, why Sanni is recorded as showing up there is a mystery.

Origin Story of Maha Kola Sanni Yaksha

Another account makes him the son of a king of a city called Sankapala Nuwera. This King, says the account, made a trip into the countryside to collect something the queen craved during pregnancy. When he returned to the palace a few days later, he was met by one of the queen’s servants. Unknown to him, this servant wanted to ruin the queen. She told the King that while he had been away, the queen had been unfaithful to his bed.

When the King heard this he was deeply injured. He ordered that the queen be put to death. Her body was to be cut into two pieces, of which one was to be hung upon an Ukberiya tree and the other to be thrown at its foot to be devoured by dogs.

When the queen heard of this, strong in her own might, she was enraged beyond measure. She claimed her innocence. She declared, “If this charge be false, may the child in my womb be born this instant a demon, and may that demon destroy the whole of this city with its unjust king.”

The King’s executioners did as they were ordered.

Half of the corpse, suspended on the tree fell to the ground and united with itself to the other half which was at the foot of the tree. The corpse gave birth to a demon that consumed its mother’s body from breast to blood to flesh and bones. It devoured her.

Unsatisfied the demon went to the Sohon graveyards in the vicinity where it lived upon dead carcasses.

Later, it returned to the city, joined by a retinue of several more demons. The demon inflicted a mortal disease on the king and dvoured the citizens. Within a very short period of time the city was nearly depopulated.

Seeing the ferocity of this new demon, the gods Ishwara and Sekkra came down to the city, disguised ofcourse as mendicants, and after some resistance from the demon, subdued him. They ordered him from that day to abstain from eating men. They gave him a warrun, which is a set of rules from which to behave. He had permission to inflict disease on mankind and to obtain offerings from them in return for their cure.

One version of the story claims Maha Kola Sanni destroyed the city of his birth, seeking vengeance on his father, the king. He created eighteen lumps of poison and charmed them, thereby turning them into demons who assisted him in his destruction of the city. They killed the king, and continued to wreak havoc in the city, "killing and eating thousands" daily, until finally being tamed by the Buddha and agreed to stop harming humans.

Maha Kola Sanni Yaksha's Attendants

According to some accounts this demon has 4,448, and according to others 484,000 subject demons under him. He rides on a lion, and has 18 principal attendants.

Each of the Sanni yaksha are believed to affect humans in the form of an illnesses, and the Sanni Yakuma ritual summons these yaksha, brings them under control, and banishes them back to the yaksha world. The ritual has been performed in the southern and western parts of Sri Lanka since ancient times.

These 18 demons are not considered to be mere apparitions of the same demon, as in the chase of the other Yakseyo, but separate individual demons acting together in concert with their chief Maha Cola Sanni Yakseya. I include a few variations.

Bhoota Sanni Yaksa, or the demon of madness: Bhuta are ghosts, so I believe this to be the yaksha that specifically relates to possession by spirits.

Maru Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of death; This is the yaksha for death and delirium.

Jala Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of cholera; Later versions of this yaksha includes chills. A variation is called Gini Jala specifically for malaria and other high fevers.

Wewulun Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of cold and trembling fits; The fourth yaksha isn’t mentioned in more recent lists of the 18. This yaksha has been replaced by the third, Jala Sanni or Gini Sanni.

Naga Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of a disease resembling that from the sting of a Cobra de Capello; In later versions this includes bad dreams and poisoning.

Cana Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of blindness;

Corra Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of lameness, paralysis, and swollen joints;

Gollu Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of dumbness;

Bihiri Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of deafness;

Wata Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of diseases caused by the wind; Later versions include flatulence, rheumatism, and shaking and burning of the limbs.

Pit Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of bilious diseases;

Sen Sanni Yaksha, or the demon of diseases influenced by the phlegm; This demon has come to also represent epilepsy. In more recent versions this yaksha is left out.

Demala Sanni Yakseya, or talking nonsense, mispronouncing words.

Murtu Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of fainting fits, loss of consciousness, and swoons;

Arda Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of Apoplexy; This demon is not mentioned by more recent records, possibly due to overlap with other demons. However, I have reference to an opposing Beeta Sanniya yaksha who is for confused behaviour and timidity.

Wedi Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of a disease which kills one instantly like a shot from a gun;

Dewa Sanni Yakseya, or the demon of diseases influenced by the gods; Some list this yaksha as representing epidemic diseases like typhoid, cholera, and the rest. In Sri Lankan beliefs it is possible to be influenced by good and bad gods. Hooniyam or a form of black magic is practiced on the island and the belief persists that someone can become sick because of an unhappy deity or a curse requested from a deity.

Aturu Sanni Yakseya, or the servant of Maha Cola Sanni Yakseya (the chief of all the 18.) This yaksha is not mentioned in more recent years.

I mentioned how a few of the yaksha in the list above are no longer mentioned in recent years. They have been replaced by these names:

Gedi Sanni yaksha for boils, furuncles, and skin disease.

Gulma Sanni yaksha for parasitic worms and stomach issues.

I suspect like with all things on the island, we’re dependent on what shamans, mask makers, and dancers have been taught over years and who and how the information was collected. Often people forget and will fill a word with another that is more commonly used like Kalpana (mind), Pissu (crazy), or Vedda (medicine).

The position of yaksha in society

Sri Lankan Devil Dance

Today Yaksha are synonymous with demons but in truth, they are spirits with neither good nor bad intent. The evidence is that Yaksha are spirits subject to higher beings, the gods or the buddha. That the gods permit a Yaksha to take a life, implies the spirit is subject to the regulation by a greater being or force.

The Yaksha featured in buddhist jataka stories often are unaware they have a choice between good actions and bad. Once faced with the consequences of the bad actions, they often choose a path that is good.

For this reason, Yaksha do not follow that they are akin to the Christian concept of a demon. They are some other spirit creature that can through their own choices are benevolent or nasty. The Yaksha is more akin to the Christian concept of a faerie or fae creature.

Manifesting Healing: Harnessing the power of the individual through theatre and community.

The Sanni ritual has long been replaced by Western and Ayuvedic medicine.

Perhaps, the Sanni ritual, which anthropomorphized the yaksha through characterizing the illness, acted as a placebo to convince the sick to get well in exchange for the offerings made to the yaksha.

Dialogues in the ritual make the powerful devils appear weak, giving the impression that the illness can be overcome. The patient is reassured that they can overcome the illness. Scientifically, this may hold some benefit.

Putting the patient center stage during a ritual and having their family and community around them, can also serve to boost a patient’s mental confidence in getting better.

Sri Lankan culture permeates with the belief that contributing to another’s wellbeing will be paid back a thousand times over. As a result, there is a benefit to the entire village community to participate and invoke blessings for not only the patient but for everyone who participates and everyone who attends.

The mask dancers are funny. Their dialogue is satire. The chief ritualist aims to help both the patient and the community.

Humour and satire is a significant aspect of the Sanni yakuma ritual drawing the spectators. The ritual also incorporates Ayurvedic remedies. The arena and the patient’s house is disinfected using tonics from local herbs known to kill germs and viruses. Turmeric mixed with water is sprayed on the patient and the arena throughout the ritual. The ritual begins with a lime cutting ceremony. Mantras are chanted in front of the patient and limes are cut placing them in a bowl of turmeric mixed water. The leaves of the kohomba tree, and fire are used during the ritual. Fragrant fossilized plant material dummala is burned by sprinkling it on a burning charcoal kabbala fire pan and carried around the arena and inside the patient’s house to infuse the circulating air with dummala smoke.

From a spiritualist standpoint, the sight of the masked dancers, the sound of the music and drums, the sound of the satirical conversations, the smell of incense, the feel of water splashing on your face, the smells of cut limes and burning wood, the feel of the kohomba leaves when they touch your skin, all of these things are designed to bring a person into connection with their surroundings. IF there is a spirit that haunts and causes the illness, the act of grounding the patient, surrounding them with a bathing of the senses and sound, overwhelming them with the ritual, could potentially chase a yaksha spirit away, leaving the patient’s body alone to rest, rejuvenate, and recover.

Or perhaps, the yaksha, entertained, fulfilled through the offerings of entertainment, sound, and smell, decides to part of its own volition.

-D.M. De Alwis

References

- Yaksha Masks | Indigenous mask traditions of Sri Lanka (Concise research by Pabalu Wijegoonawardana, Report appendix here with references.)

- Amaruwan Dilina, 2019, Demonism and Witchcraft in Sri Lanka as seen in 1865

- Obeyesekere, Gananath. “The Ritual Drama of the Sanni Demons: Collective Representations of Disease in Ceylon.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 11, no. 2 (1969): 174–216. http://www.jstor.org/stable/178251.

- De Silva Gooneratne, Dandris. “On Demonology and Witchcraft in Ceylon.” The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 4, no. 13 (1865): 1–117. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43483453.

Subscribe to the Myths & Samsara podcast on YouTube (Visual), Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, and Pandora.

Sign up for the free monthly digest—a summary of new podcast episodes, my author journey, and the latest books available at bookstores.

Support the work and keep it coming.

- Comments on posts.

- Free access to the archive.

- A monthly update to your inbox.

- No Spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Member discussion